On October 8, an article on Nepal’s revolution appeared in The New York Times. (Click here if you don’t have access.) Written by Hannah Beech, the article is an ugly mix of journalism and storytelling that leaves huge plot holes in the characters described. (Also, I choose to comment on the report published in a foreign newspaper to show my fellow to be careful of the narratives they are trying to set.) Among the basic questions that journalism should answer, who, what, where, and when appear, but there are huge gaps in why and how. In this essay, I will point out and try to analyse where these questions are missing.

The article presents the story of Tanuja Pandey, Misan Rai, Mahesh Budhathoki, Sudan Gurung, Rakshya Bam and Dipendra Basnet as representatives of the protests. Presentation of these stories, however full of plot holes, inconsistencies, and mystery that journalism fails to cover.

Plot holes, Inconsistencies, and Mysteries

1. Generalization of Gen Z

In the fifth paragraph when Beech writes:

Across the world, Nepal’s youth have been celebrated as spearheads of a Gen Z revolution, the first to so rapidly turn online outrage at “nepo kids,” as privileged children of the elite are called, into an overthrow of the political system. The trajectory of Nepal’s Gen Z — economically frustrated, technologically expert, educationally overqualified — is part of a wellspring of youthful dissent that has flowed in recent years from Indonesia and Bangladesh to the Philippines and Sri Lanka.

Calling Nepal’s Gen Z technologically expert and educationally overqualified is a picture that applies only to the urbanites and the privileged. I too had made this mistake earlier. There are thousands of youths between 13 and 28 in rural areas who are struggling to get even a primary education. And there are more, even among the well-educated, who don’t know how to use a computer and for whom the internet is nothing but Facebook and TikTok.

2. How the new government formed

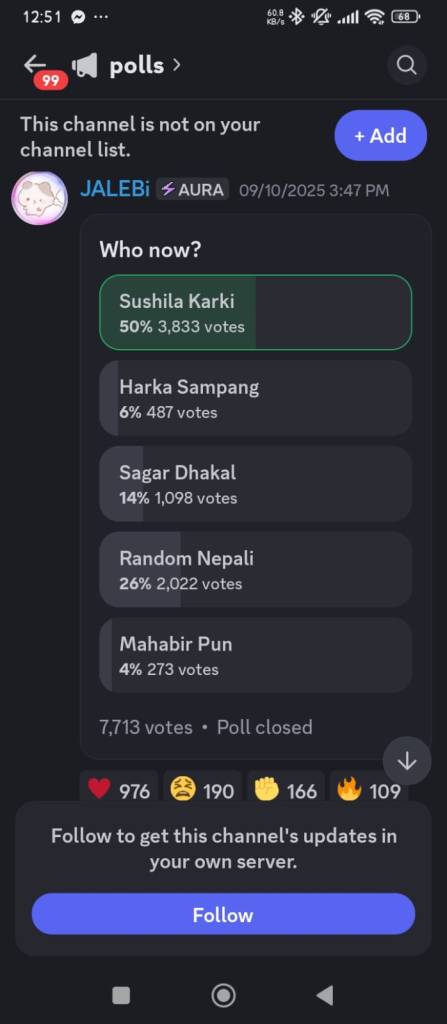

The article has two paragraphs on how the new government was formed. In the first paragraph, it says that “Gen Z keyboard warriors” supported Sushila Karki as the interim prime minister.

After the government collapsed last month, thousands of Gen Z keyboard warriors supported the appointment of Sushila Karki, a corruption-busting former chief justice, as leader of a caretaker administration, making her Nepal’s first female prime minister. Elections in this Himalayan nation, one of Asia’s poorest, are scheduled for March. The three big political parties, which for years traded power and alliances with an exuberant disregard for ideology, have been cowed for now.

A paragraph that appears later tells that the Chief of Army, General Ashok Raj Sigdel mentioned Sushila Karki’s name as the prime minister even before her name came up on Discord.

At army headquarters, General Sigdel had mentioned Ms. Karki’s name to members of the Gen Z movement before she became an online favorite. It was strange, they said, like he knew what was happening on Discord before it actually happened.

Journalism, however, ends here. There is no exploration of how the General Sigdel put the name forward. Questions remain: Did he do it on his own? Was there other external influence?

If General Sigdel said the name himself, we are under a military control. If there was external influence, its even worse.

Moreover, the Discord poll was for selecting a representative to put forth unified demands of various Gen Z groups, not to choose a prime minister (even I had thought so before I looked back).

3. Unnecessary storytelling over journalism

The characters mentioned above appear dispersed throughout the article. The fact that they are flawed makes them human. However, the storytelling choice makes them unserious and cringey. Although I have been criticising the “Gen Z leaders”, I felt sympathetic towards them for being featured in a “story” of sensational journalism.

Insensitive Portrayal of Misan Rai

Misan Rai, a 18-year old protester had gone to the protest for the first time on Bhadra 23 (September 8). Her story, although truthful, makes her look insensitive and comical.

Tear gas exploded around her. Her friend’s mother ordered them to withdraw. The trio escaped down an alley, trailed by clouds of tear gas. The sounds of gunfire came soon after, but it was hard to tell the rev of a motorcycle from the volleys of bullets. Ms. Rai hadn’t eaten all day, apart from a couple of wafers gulped down before her exam. In the alley was a grapefruit tree, and she plucked the bittersweet fruit.

“I feel terrible I was eating when people were dying,” she said.

Inconsistency in Rakshya Bam’s Story

Rakshya Bam has been confidently telling that “saving the constitution” and going to elections in Falgun (March) is the best option and confidently puts its forward in her interviews with Rupesh Shrestha and Himalkhabar. The New York Times has shown a different side.

“We are all wondering, what to do if everything goes back to the same way, even after we lost our blood and fallen comrades?” said Rakshya Bam, 26, a protest organizer, who missed a bullet by a fateful flick of her head. “What if all this was a waste?”

The story of her missing a bullet appears later in the story again.

Ms. Bam, a protest organizer, felt a bullet rush past her head, the warmth imprinted even now in her mind, like a shadow that cannot be outrun.

Her interviews have never talked about the incident. She mentions making a human chain and witnessing a injured person, but she has never said about a bullet missing her. It’s an extremely significant event to miss. Also, eyewitness accounts have told that she and her team never went beyond the Everest Hotel. What’s the truth then?

Mysteries around Mahesh Budhathoki

The story of Mahesh Budhathoki is full of mysterious, sensational events. On September 8, he is said to have ridden among a fleet of motorcycles, whose riders wore black:

By late morning, men on motorcycles arrived, two or even three on each bike. Many wore black. Some waved the Nepali flag with its two red-and-white triangles. Some were Gen Z, but others were not. Ms. Pandey and some other organizers didn’t like the intrusion. They had released an earnest set of protest prohibitions, including no flags or party symbols. They didn’t want old politics to infiltrate a nonpartisan movement.

Mahesh Budhathoki, 22, rode among a fleet of motorcycles, the bikes revving with sharp salvos of noise. These bikes, as well as the entrance of other men — older, tougher, tattooed — changed the protest’s atmosphere, attendees said. The crowd got angrier, the slogans more extreme.

The protesters rushed the gates of Parliament. Men materialized with pickaxes. They attacked a fence. Ms. Rai watched the “goondas,” as she called them, “like bad guys in Bollywood” films. She wrapped her arms around a fence pillar to defend it from the destruction.

Again, storytelling tops journalism here. There is no objective investigation on those bikers and men with pickaxes. Only after a hint was left by Diwakar Sah in his video on October 11, the identity of those bikers became more well-known (See this TikTok video). Were they involved in violence? They have denied it on their Facebook page. There are other videos like this where the biker gang is aggressive, though. I think it’s a matter of deeper investigation.

Beech’s description of the events on September 9 gets even more mysterious with the mention of unfamiliar men handing Molotov’s cocktail.

In another part of town, Mr. [Mahesh] Budhathoki and his friends awaited instructions. Unfamiliar men handed them bottles filled with fuel, cloth stuffed in the top. The mob attacked a police station, anger swelling at the force blamed for killing the protesters the day before. From inside the station, a police officer grabbed a rifle and opened fire.

His death is shocking.

Mr. Budhathoki was a soccer fan who had been set to move to Romania for work before he joined the protest. His mother had been diagnosed with cancer, and the family needed money. A bullet hit him in the throat. He died slung over a scooter on the way to the hospital.

A more shocking event happens afterwards when his friends lose their mind and kill three policemen.

One of Mr. Budhathoki’s friends said he felt like the tendon girding his sanity had snapped. The crowd hurled the Molotov cocktails at the police station. They stalked the officers inside. One terrified policeman stripped off his uniform and tried to flee. The mob found his clothes and discarded pistol, then beat the man in his underpants until he stopped moving, two participants said. Video footage verified by The New York Times shows a crowd surrounding the motionless body. Another policeman ran into a neighboring building, climbing high. The crowd chased him and pushed him off a balcony, the friends said.

A traffic policeman, who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, did not escape the mob either. The police said three officers died near the police station.

“We were all killers,” said a 19-year-old protester named Habib.

He said he was proud of having avenged his friend’s death. In his hands, he held the casing of the bullet that he said killed Mr. Budhathoki. He found it on the ground, still hot. Days later, the shell smelled of smoke. He tightened his fist around it.

“We are Gen Z, but we’re just doing the dirty work of the old men,” he said.

Habib’s statements: “We were all killers” and “We’re just doing the dirty work of the old men” chilled me when I read them. When I went back at them, I realized that they are also overgeneralizations, for there were also people who were urging protesters to keep calm and avoid being like the old men.

Questions still remain: Who gave them Molotovs? Did the policemen who were killed by the mob shoot bullets? What will happen to Habib and the mob in the future?

Another inconsistent story of Sudan Gurung

Sudan Gurung, a volunteer of Hami Nepal has established a communication channel, Youth Against Corruption on Discord. This is where polls mentioned above occurred, and Sushila Karki was the clear winner. The following story is thus inconsistent with what is known to the public.

Mr. [Sudan] Gurung said that the people wanted to nominate him as prime minister. But he demurred, he said. He wanted Ms. Karki. Mr. Gurung waited for eight or nine hours in the palace for Mr. Paudel to approve her name. Mr. Gurung wore slippers and occasionally padded around barefoot.

“I didn’t care,” Mr. Gurung said. “We just toppled the government. It’s our palace now.”

When his story comes up again, he is said to have “floated vying for prime minister himself.”

Two days later, Mr. Gurung organized a late-night protest. His target: Ms. Karki, who had not consulted with him when she named three new cabinet members, he said. He demanded her resignation. He later floated vying for prime minister himself.

While I remember him and a group consisting of family of martyrs protesting the newly appointed prime minister, I don’t remember him talking about the post for himself. He did so with an Aljazeera interview though.

The Weirdest Story of Tanuja Pandey

Hannah Beech introduces Tanuja Pandey as “a Himalayan Greta Thunberg”.

Ms. [Tanuja] Pandey, a lawyer, had started off protesting as a high school student, like a Himalayan Greta Thunberg, campaigning to save Nepal’s environment. She was used to small, peaceful acts of dissent, usually with more police officers than protesters.

The problem with this description is that Greta has been controversial because of her privileged upbringing and advocacy of issues that are against Conservatives. Moreover, Nepal’s low contribution to carbon emission compared to the developed nations makes us victims. Was she involved in demanding climate justice with them? I doubt. Had she been doing so, she would have made news, at least in Nepal.

The story then pictures the protest from Tanuja’s eyes:

This march, though, felt different, she said. The online call by Ms. Pandey’s group of activists and lawyers urging fellow Gen Z-ers to rally against corruption and the social media ban had spread fast. Hami Nepal, a civic organization that helped with earthquake and flood relief, added its influential voice. Other youth groups popped up online calling for protesters to join, including one that had rebranded itself from a Hindu nationalist “God of Army” to a clique that supported Nepal’s deposed monarch to — on the day of the protest — Gen Z Nepal (similar to the moniker of the original protesters).

Hearing that students had been shot made Ms. Pandey feel ill. She couldn’t understand why so many older people had joined, kicking up trouble, revving their motorcycles, throwing stones. She was mystified by the lack of police until, suddenly, they were firing tear gas and then bullets.

However, Hannah leaves out the questions her journalism should have answered: Why was the number of police reduced? Did the pro-monarchs/pro-Hindus do anything wrong during the protest? Why did Hami Nepal become influential?

This paragraph again brings up conflicting scenario without explaining why and what happened next.

By the time the security forces had shot and killed 19 people and injured dozens more, Ms. Pandey had left the protest. Things had moved so quickly and gotten so violent that her group issued an online call urging everyone to leave. But forces that said they were associated with Mr. Gurung’s group, Hami Nepal, issued a counter order, urging people to return.

Tanuja is still shocked that the revolution has taken place:

“We wanted reform, not a revolution,” said Tanuja Pandey, 25, who helped first publicize the protest on her Gen Z group’s social media.

“I don’t know what happened, but the whole thing was hijacked,” she said.

If she claims she is a “leader” of the protests, she can’t just say “the whole thing was hijacked.” She is not a common person now. She should at least try to expose who hijacked the protest.

The NYT’s journalism also does not help. It does not explore the hijackers or if Tanuja’s statement was legitimate or not.

Moreover, the last scene of the article is out of place and cringeworthy:

A week after the protests began, Ms. Pandey celebrated her 25th birthday in Kathmandu. She was still keeping a low profile, fearing arrest or worse.

A hard rain obscured the gaggle of Gen Z protesters splashing across the paving stones to a small restaurant run by sympathizers. Lawyers and environmental activists, influencers and cultural preservationists, Ms. Pandey’s friends toasted with brass cups of milky rice wine. They feasted on deep-fried intestines stuffed with lard and dipped in fermented chile. They sang songs from the Beatles, Bob Dylan and Bollywood.

“To an accidental revolution,” they toasted.

Ms. Pandey looked serious.

“What happens now,” she asked. “Will Nepal change?”

Her friends turned quiet. They swallowed more wine. The rain beat down, fierce and warm.

Final Opinion

The New York Times article on Nepal’s revolution is rich is storytelling but poor in journalism. It does not answer even the basic of questions in many cases. Moreover, there are discrepancies in the description of events and characters.

I think the most devastating is generalization of Nepal’s Gen Zs as nonchalant and politically unaware. Misan Rai eating grapefruit amidst the protest and Tanuja Pandey gulping down wine on her birthday party despite an uncertain political future portray Nepalese Gen Z activists as carefree youths involved in something they can’t barely understand. Also, some of the scenes show how Nepalese youths crave for power and have a violent tendency.

The article, as a whole, fails to raise hope about the “revolution”. But that’s how I have felt since the evening of September 9. So, if it did not bring hope, can we still call it a revolution?

Discover more from Stories of Sandeept

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply